|

Sri

Aurobindo asserts:

'AND STILL THERE IS A BEYOND.

For on the other side of the

cosmic consciousness there is, attainable to us, a consciousness yet

more transcendent, - transcendent not only of the ego, but of the

Cosmos itself, - against which the universe seems to stand out like

a petty picture against an immeasurable background. That supports

the universal activity, - or perhaps only tolerates it; It embraces

Life with Its vastness, - or else rejects it from its infinitude'

(The Life Divine, Pg 22)

That is the Transcendence. An

experiential contact with it leads the seer-poet to exclaim:

‘I

HAVE DRUNK THE INFINITE LIKE A GIANT’S WINE

TIME IS MY DRAMA OR MY PAGEANT DREAM’

(Sri Aurobindo Collected Poems,

Pg.133)

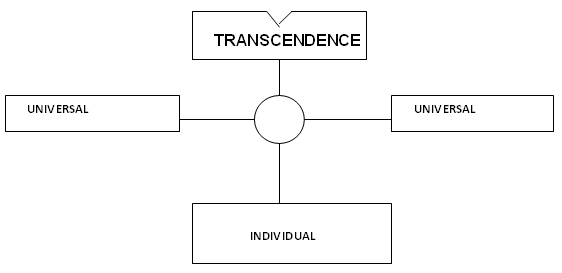

THE SYMBOLISATION OF THE

TRANSCENDENT

The Transcendent is symbolized by

a perfect ONENESS that potentially contains the DUALITY of both the

unity and the multiplicity, the Infinite and the Finite, the

Timelessness and the Time. THAT THE TRANSCENDENT IS SIMULTENOUSLY

ONE AND TWO (OR DUAL) AT THE SAME TIME was always known in spiritual

traditions. The Mother explains that this was the original meaning

of the Cross in Christianity.

(The Mother, Collected Works Vol. 4, pg. 393)

In

fact, The Mother who gave names to flowers in accordance with their

hidden psychological significances and symbolisms chose the

‘Cork-oak of India (Milling

tonia hortensis) to symbolize “transformation”. This flower has four

petals. The petal at the top represents the ‘transcendent’, the two

on each side represent the ‘universal’ and the one at the bottom

represents the ‘individual’.

These four petals are arranged like a cross, and The Mother points

out that as a symbol, this petal-arrangement is more perfect than

the Cross. Because the Transcendent is one and two (dual) at the

same time, the petal at the top is divided into two. What a

wonderful symbol!

Transformation (name given by the Mother to the flower of Cork-oak

of India) Cork-oak of India (Millingtonia hortensis)

Different Poises of Consciousness

In

fact, one needs to reemphasize that the Transcendent, the Universal

and the Individual are different poises of Consciousness that

COEXIST AT THE SAME TIME. The Transcendence of course is beyond the

creation and independent of creation and therefore exceeds the

‘transitory’ status of the creation which includes the cosmos and

the individual - - transitory because the solar systems can collapse

and the individual can perish while the status of the Transcendence

remains unaffected. ‘We speak as though things had unfolded in time

at a date which could be fixed: the first of January 0000, for the

beginning of the world, but it is not quite like that! There is

constantly a transcendent, constantly a universal, constantly an

individual, and the transcendent, universal and individual are

co-existent. That is, if you enter into a certain state of

consciousness, you can at any moment be in contact with the

transcendent…., and you can also, with another movement, be in

contact with the universal…, and be in contact with the

individual…., and all this simultaneously – that does not unfold

itself in time, it is we who move in time as we speak, otherwise we

cannot express ourselves.’ (The Mother, Ibid, pg. 393).

In

fact, it is the linear thinking with which we are ordinarily

accustomed that cannot conceive the simultaneity in Reality. ‘The

mind thinks about things in succession. But beyond and above,

everything exists at the same time. The One is both one and two: the

manifested and the unmanifested, everything exists at the same time.

When it is objectivised in the creation, in the manifestation, there

is a succession: one, two…But this is only a way of speaking. There

is no succession, no beginning. Beyond, in the perfect Oneness,

everything exists at the same time, simultaneously. This cannot be

understood, it must be experienced; one can have the experience of

it’.(The Mother, Collected Works, Vol. 16, pg 374-375)

'TRANSCENDENCE' AND 'GOD'

Actually, the Transcendent is called God in different religions.

Major religions in the world consider the ‘Transcendent’ to be the

only Reality making actually ‘God’ more extra cosmic than supra

cosmic. The World or the Universe as well as the Individual are

secondary or subservient to God in the Semitic traditions.

In

the Indian tradition, the supreme consciousness or God is equally

represented in the Transcendental, Universal and Individual poises.

Yet an experience of the Transcendent can suddenly give a sense of

‘unreality’ to the world. It is an overpowering experience that

influences ascetism to reject the drama of life. Thus, the creation

(comprising the universe and the individual) is considered to be

either as secondary, subservient to the Transcendence (as in the

Semitic traditions) or unreal (as in the Monist & Buddhist

traditions).

But Sri Aurobindo prefers a wider synthesis where the Transcendent,

the Universal and the Individual - all have their proper

representations. He expresses this triune status of the Divine

movingly in his sonnet, ‘The Indwelling Universal’:

The

Indwelling Universal

I

contain the wide world in my soul’s embrace:

In me Arcturus and Belphegor burn.

To whatsoever living form I turn

I see my own body with another face.

All eyes that look on me are my sole eyes;

The one heart that beats within all breasts is mine.

The world’s happiness flows through me like wine,

Its million sorrows are my agonies.

Yet all its acts are only waves that pass

Upon my surface; inly for ever still,

Unborn I sit, timeless, intangible;

All things are shadows in my tranquil glass.

My vast transcendence holds the cosmic whirl;

I am hid in it as in the sea a pearl.

(Sri Aurobindo Collected Poem,pg.142)

|